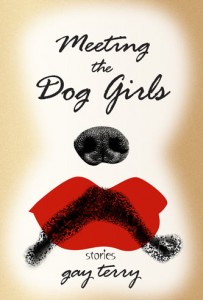

The following excerpt is from the new book

Meeting the Dog Girls

by Gay Terry. In bookstores now.

The Line

THERE IS NO BEGINNING, no end to the line, just women waiting. The women are beautiful in a disheveled sort of way. A slick of sweat illuminates skin in sunlight and moon glow whether the complexion is dark or pale; the powdery dust adds glistening texture. We don’t look around much; we wait. Though there are many of us, we’re all too exhausted to be companions to each other. Once in a while we move forward ever so slightly. The children do not play; they’re much too lethargic from hunger. They stare out from behind mothers and strangers or weep quietly.

It does no good to worry. We stare into space. We attempt to patch our ragged garments. We wait enshrouded in our own thoughts. Yesterday there was a great storm so we’re feeling cleansed. We’re lucky to have warm weather and sun now. When the rainy season comes, we’ll have to dig out our old tarps and endure the smell of mold.

The woman ahead of me picks nits out of a small girl’s hair; perhaps it’s her daughter. Like the line, there is no end to the nits. She crushes them in her fingers and eats them or feeds them to the girl. Both are so thin that you can see bones through the skin, but their faces are beautiful. Their dark watery eyes are deep-set, and chapped lips perfectly rounded. In front of them an old woman sits like a stone reliquary, lines of dignity set into her face and pendulous breasts resting beneath her thin dress. The woman behind me never looks up. Her sad eyes are intent upon the earth, her head intricately wrapped in yards of faded muslin. I asked where she came from, but her answer was unintelligible. It’s possible that none of us really know what we’re moving toward. At least we’re not being shot at and the KEEP workers come by occasionally with water and a little food.

Mornings go quickly. Afternoons are intolerably long, hot, and dull. Evenings we eat the hard biscuits and bruised fruit we’ve hoarded all day. At night there are stars to watch, some shoot across the sky from above; some rise up from the ground. The expanse of sky makes our brief lives and hardships seem small. In the relative coolness of night, we sleep. Somehow, mornings are hopeful – even without promising expectations.

I sit on my bundle of belongings when I’m tired, curl up around it at night. There isn’t anything in it but rags, a cup, and a dish or two. I wrap myself in the tapestry my great grandmother wove. It was kept in the ancestor chest at my mother’s house, only brought out on special occasions. It’s all I have left of a life that may have been a dream or a dream that may have been a life. Like me, it has begun to fade and unravel. During the day I attempt to patch it, but it wears faster than I can sew. I’ve run out of scraps with which to piece it back together and my fingers are becoming stiff and unresponsive.

I keep three photos in the pocket of my dress. One is a smiling child with parents, one a street in a small town, the other is so worn that I can no longer make it out. I pretend that these are familiar. The truth is that I only remember the line and the tunnels …

Our men are all dead or at war, even many of the boys have gone. There are bodies in the fields and on the road, too many for the animals to take, animals that have grown fat and lazy from overeating. Blood has made the ground so fertile that the bush grows thickly, covering them. The river is polluted with blood and body parts. Many of the men have been in tunnels for months. I myself was in one for several days. There’s little air in the tunnels and some very bad odors come from the wounded that hide there. The husband who protected me has been gone for a long time. I can no longer remember his face but I see images in the clouds and the dry earth about me, of the child we lost.

Occasionally a truck passes by and sometimes they stop and take a woman or two with them. I smile, though never right at them, and try to stand straight. I’m hoping one of them will take me. Though the men in the trucks carry weapons and seem rough, I would be happy to go with them. I don’t mind a little roughness. Sometimes they sing and shoot their guns in the air. The women in the line never sing, though I may have heard someone humming once.

I hope that we’re waiting for transport though I’m not sure the people on the trucks know their destination any more than those of us on the line. But at least there’s movement, wind in your hair and singing.

Last night a boy came and pretended to be my son. I shared a biscuit with him, but this morning he was gone. Men and boys don’t have patience for the line; they’d rather take their chances on the road or fight.

It’s easy to believe that the gods have abandoned this place, but sometimes at night the distant thrum of gunfire becomes a low-pitched note that vibrates inside the body and resonates with the peace of the line and the mercy of picking nits from someone’s head or sharing a biscuit. I have learned enough to know that there’s always been lines, and there’s always been war.

I would leave the line if I had any place to go or anyone to go to. I’m trying to remember … Perhaps I’ll go anyway, just for the walk. I could look at the bodies, those in reasonable condition, to see if any look familiar. Perhaps I could find more pictures or some useful items. But then what would I do with them? I couldn’t sell them even if they were useful, because no one has money to buy with or goods to trade. And I can’t carry any more in my bundle; as small as it is, it’s still a burden in the heat. I don’t want to end up in the tunnels again. Perhaps someone in front of me will get tired of waiting or get picked up by a truck and I’ll be able to move forward. I could join the fight, but what good would that do? What side would I fight on? I know nothing of sides.

I only know waiting …

© Gay Partington Terry

Trade paperback and ebook now available from Nonstop Press or wherever books are sold

Write a Comment